An Online Lifestyle Medicine Course for Medical Students

By Polly Dunn

8th Nov, 2021

As medical students at a UK university, we are not alone in having noticed the lack of Lifestyle Medicine (LM) training that is embedded in the core curriculum 1,2,3. We feel that a limited understanding of LM could leave students ill-prepared as future doctors to advise patients on important aspects of their health. To this end, we collaborated on a series of online lectures for students, covering the main pillars of LM, namely nutrition, physical activity, stress, sleep, healthy relationships, and substance use, plus an additional lecture on welfare issues specific to medics.

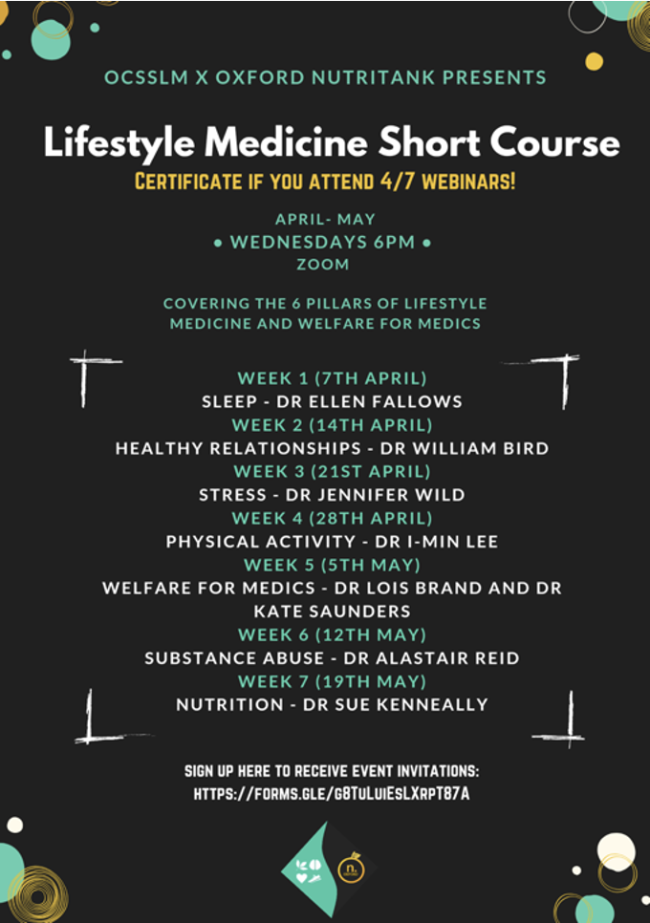

The course was primarily aimed at clinical medical students at Oxford. However, we were pleased to find that a range of pre-clinical students, junior doctors, medical students from other universities and prospective medical students also attended the course. The lectures summed up to a total of 7 hour-long sessions, held at the same time each week to encourage attendance. As an additional incentive, we provided certificates for those who attended 4 or more of the sessions.

The students that collaborated to create a lifestyle medicine course

We invited a variety of speakers from the University of Oxford, as well as elsewhere around the world, to speak on their subject of expertise. Speakers included the likes of Dr Jennifer Wild (developer of SHAPE, an evidence-based programme to support frontline healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic) and Harvard’s Dr I-Min Lee (expert on the benefits of physical activity in preventing chronic disease). Each session included an interactive quiz that focused on learning objectives that the speakers themselves set. These aimed to help participant engagement and focus during the session, and to provide discussion points at the end of the session.

An overview of the lifestyle medicine course running from April - May

Participants were asked to complete a feedback form for each session they attended. These included numerical rating scales to assess whether the participants would recommend the session to others and whether they thought the topic should be part of the core medical curriculum. The mean likelihood of recommending the session to others at their stage of training was 4.5 (with 1 being “very unlikely” and 5 being “very likely”). When entries were grouped by session topic, the means ranged from 4.3-4.8, demonstrating that the quality of sessions as perceived by the participants was relatively consistent. Similarly, when asked to rate the degree to which they believed the topic should be part of the curriculum at UK medical schools, the mean was 4.5 (with 1 being “strongly disagree” and 5 being “strongly agree”). This also remained within a relatively narrow range when differentiated by session topic (4.3-4.7). These values confirmed to us that on the whole participants had found the sessions both interesting and relevant to their medical education.

As well as semi-quantitative rating scales to assess the course’s effectiveness, we also collected comments from the attendees relating to what they liked, disliked and learnt from the sessions they had attended. Many attendees mentioned how much they liked the inclusion of practical and easily usable tips for both patient interactions and their own wellbeing. Other popular elements of the course included the use of interactive online polls in every session and the clear referencing and discussion of scientific evidence relevant to the topic.

Conversely, it was interesting to read what participants suggested could improve the course. A common theme was the desire for a stronger emphasis on the application of these ideas to clinical practice, alongside suggestions to include more case examples and patient experiences. In addition, a number of attendees thought that the sessions should have been longer, highlighting the need to carefully plan the scope of such a course as it can easily feel rushed trying to cover such a broad subject area.

The audience size per session ranged from over 40 participants, to less than 20. It was noticeable that fewer individuals attended the sessions as the course went on, but as outlined above, this did not appear to correlate with lower ratings given in the feedback for the quality of the sessions or relevance of the topic. It may be that this is related to external factors (such as the approaching exam season) or issues relating to organisation of the course such as reduced time spent publicising the events on social media. For this reason, we suggest that anyone organising a similar course in the future carefully consider the timing of the course and ensure there are designated roles and methods for advertising the events sufficiently.

Our team is pleased with the way that our pilot LM course for medical students was received and is extremely grateful to the clinicians who made it possible by giving up their time to run sessions or help us with the organisation. We hope that similar courses will be run at Oxford University and elsewhere in the future, and that the organisers can take what we have learnt from the experience to further increase their courses’ reach and popularity.

Bio

This Lifestyle Medicine Course was run in collaboration between Oxford Nutritank and Oxford Clinical School Society of Lifestyle Medicine (OCSSLM), two student-led societies at the University of Oxford. These societies aim to promote awareness and discussion of issues relating to Lifestyle Medicine amongst medical students. Contributors to this article include Polly Dunn (Chair of OCSSLM), Harriet Taylor (Secretary of Oxford Nutritank), Emer Chang (President of Oxford Nutritank) and Orlaith Breen (Vice Chair or OCSSLM and Educational Lead of Oxford Nutritank).

Social Media

OCSSLM – Facebook

Oxford Nutritank – Facebook

Instagram: @oxfordnutritanksociety

References

- Radenkovic, D., Aswani, R., Ahmad, I., Kreindler, J. and Robinson, R., 2019. Lifestyle medicine and physical activity knowledge of final year UK medical students. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 5(1), p.e000518.

- Macaninch, E., Buckner, L., Amin, P., Broadley, I., Crocombe, D., Herath, D., Jaffee, A., Carter, H., Golubic, R., Rajput-Ray, M., Martyn, K. and Ray, S., 2020. Time for nutrition in medical education. BMJ Nutrition, Prevention & Health, 3(1), pp.40-48.

- Griffiths, H. and Artusa, S., 2020. Medical students as agents of lifestyle medicine. The Clinical Teacher, 17(5), pp.579-580.

Login

Login