Lifestyle Medicine Skills

Click here to become an Accredited Lifestyle Medicine Healthcare Professional

Ensuring lifestyle medicine education gets to those that need it the most is critical, but education alone is not enough to create sustainable lifestyle changes. There are various skills that have proven to be successful in supporting patients in this regard.

Lifestyle medicine calls for a move away from the traditional doctor-patient relationship where the clinician is the expert information provider. This is needed because we now know that giving simple lifestyle advice such as “eat less and move more” is often ineffective1 2.

To be effective in supporting lifestyle change, lifestyle medicine uses knowledge of behavioural science to work with patients. This way we can work with people and their values to support problem solving and equip them with skills to make the changes they want to make. Some of these techniques have been shown to be at least 80% more effective in supporting behaviour change than traditional advice giving3 and include:

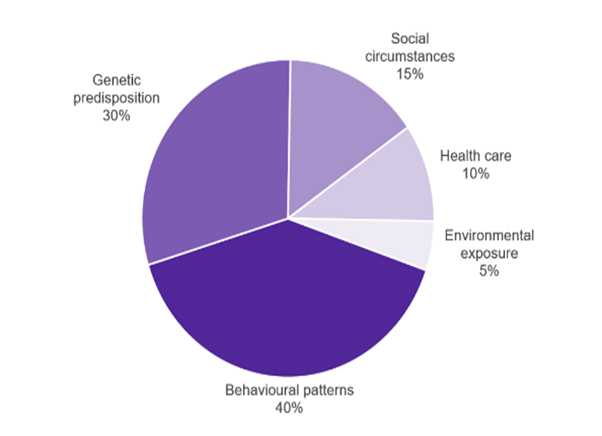

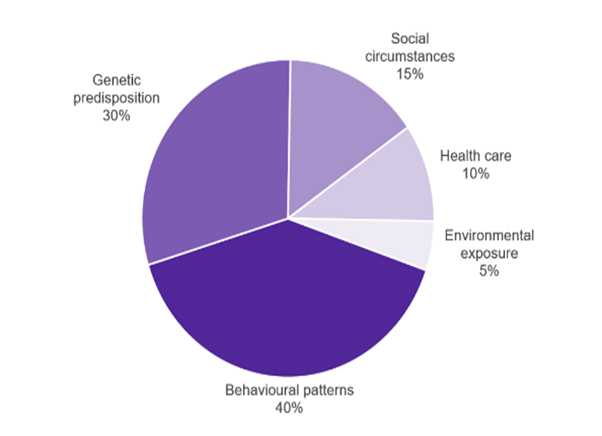

Figure 1: Determinants of premature mortality and their contribution4

Person Centred Care

“A person-centred approach means putting people, families and communities at the heart of health, care and wellbeing.”5 It is also known as personalised care. Lifestyle medicine uses person-centred techniques that ask people what is important to them about their health in order to support their autonomy. Techniques used in person centred care include shared decision making, care and support planning, goal setting and supported self-management. People are much more likely to make and sustain behavioural change6 if this approach is used.

If you’re interested in learning more about Person Centred Care, click on one of the links below:

Values Based Care

Value-based healthcare is a healthcare delivery model where funding is based on patient health outcomes i.e. outcomes involving helping patients to improve their health, reduce the impact of chronic diseases, and live healthier lives. This compares with a fee-for-service or capitated funding system, which values the amount of healthcare services delivered and pays for these. Values-based health care can also describe the clinical skills requires to use and integrate the evidence base for a particular treatment pathway with the values (for example the needs, wishes and expectations) of individual patients. This approach is more often now called person-centered care.

Supported Self-Care

Supported self-care or self-management is part of the NHS Long Term Plan. Health and care services should work to encourage, support and empower people to manage their ongoing physical and mental health conditions themselves. Empowering people with the confidence and information to look after themselves when they can, and visit the GP when they need to, gives people greater control of their own health and encourages healthy behaviours that help prevent ill health in the long-term.

You can find out more about how to support people with self-care, including self-care resources below:

Homepage – Self Care Forum

Supported Self-Management (personalisedcareinstitute.org.uk).

Motivational Interviewing (MI)

Motivational Interviewing is a person-centred conversational style for helping people become more ready to change one of more behaviours. As a counselling style, it pays as much attention to the relationship (e.g., empathy, warmth, alliance and non-judgement) as it does behaviour change techniques such as self-monitoring, education, goal setting, decisional balance, skills development, scheduling and signposting. It is a way of talking with people, not a technique.

There are over 2,000 research studies into the effectiveness of MI. The strongest evidence of effectiveness is in the area of addictions 7 and MI has also been found to be effective in supporting behaviour change and self-management in many long-term conditions 8-10 including in cancer care 11, chronic pain 12, Type-2 Diabetes 13, heart failure 14, hypertension 15 and healthy dietary change 16.

If you’re interested in learning more about Motivational Interviewing, click on one of the links below:

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

CBT recognises the link between thoughts, feelings and actions. It aims to help people to recognise vicious cycles of negative thoughts and feelings. CBT has been shown to be effective at supporting people to lose weight, improve emotional well-being, increase activity and improve diet.17-18

Health Coaching

Coaching has been described as a way of “unlocking a person’s potential to maximise their own performance”19 by supporting people to find their own unique solutions by focusing on the present and being goal oriented.

The key ingredients to health coaching are:

- A compassionate approach

- Active listening and reflection by using open questions

- Goal setting

- Supporting ownership and the patient generating their own ideas

- Encouraging taking small steps in the patient’s chosen direction

Coaching has been found to be particularly effective in supporting people with Type-2 Diabetes.20

Brief Interventions

Brief interventions are ways to support behaviour change in even under 30 seconds. They are “verbal advice, encouragement, negotiation or discussion with the overall aim of increasing [a behaviour] delivered in a primary care setting by a health professional, with or without written support or follow-up”. Brief interventions have been found to increase physical activity, weight loss and reduce alcohol consumption. They have informed the Making Every Contact Count (MECC) initiative set up by Public Health and Health Education England. This focused on the use of brief and very brief interventions delivered when the opportunity arises.

If you’re interested in learning more about Brief Interventions, click on one of the links below:

Goal Setting

A commonly used goal setting technique is that of SMART goals. This can be used to set helpful and constructive goals. Goals should be:

- Specific

- Measureable

- Achievable/Attractive

- Realistic

- Time-bound

Health coaching can also help people identify their goals. Questions that may be helpful in order to suit them in doing this include:

- What are you trying to achieve?

- What do you want?

- What does success look like?

- When you achieve this, what will you be doing?

- What would you like to take away from today’s conversation?

Lifestyle Medicine Prescriptions

Lifestyle Medicine prescriptions may be useful in any area of lifestyle but are most commonly used in the areas of physical activity and nutrition. Healthcare professionals can discuss with their patient what they are willing to do and using SMART Principles (see section on goal setting)

Nutrition prescriptions aim to improve patient nutritional health through evidence-based, specific plans tailored to individual needs. Applying the SMART principles: Simple and Specific (Align the patients targets with their behaviour, name specific foods), Measurable (How many should they eat?), Achievable (Who makes food decisions, is the patient confident in the goal?), Realistic/Relevant (What is available, What is the current situation?), Time Bound (How Frequent, How Long?) we can make actionable and measurable objectives for the patient. These may include, increasing consumption of certain types of foods or swapping for alternatives (positive prescriptions) or reducing intake of others (negative prescriptions). In general, positive prescriptions are more useful than negative ones. This can help us create the prescription which has 3 core-components: The type of food to be eaten, amount of food to be eaten, and the frequency that the food should be eaten adding the duration of the change if needed.

Prescribing physical activity may follow the ABC method: Assessment (Assess the patient, what are their preferences and current situation), Brief Intervention (Tailor change to the individuals lifestyle to increase compliance to the intervention), and Continued Support (Follow up on a regular basis, through phone or in person to maintain accountability). An acronym to remind us what to include in the prescription is FITT: (Frequency (How often?), Intensity (How intense?), Time (How long?), and Type of activity (Tennis, Running, Cycling etc?)

This alternative goal-setting method and allows for gradual increases in the patients activity such as increasing the frequency, length or intensity and can be adapted for various forms of exercise.

Social Prescribing

Social prescribing takes a holistic approach to health by connecting people to community groups for practical and emotional support. It recognises that our environment and social connections play a huge role in influencing our health behaviours. Social prescribing link workers are now working in primary care as part of NHS England’s long-term plan.21

If you’re interested in learning more about Social Prescribing, click on one of the links below:

Click Here to Learn More About Social Prescribing in Lifestyle Medicine

Group Consultations

Group consultations are a tried and tested way to deliver better quality care to patients in a cost-effective and rewarding way. 10-15 people with similar conditions come together and agree to some shared understandings and discuss a results board where they share their clinical results (having given consent). The group consultation facilitator supports the group to reflect upon what their priorities are and ask questions such as “what matters to me about my health?”. The clinician is briefed before joining the group and then reviews each patient’s questions 1:1 before encouraging the group to share experiences and problem-solve together. Group consultations are proving to be a very powerful tool to support people to make lifestyle and behaviour change by delivering group support, education as well as the benefits of 1:1 attention from a clinician. There is good quality evidence that group consultations are better than a 1:1 appointment for the care of people with Type-2 diabetes22. There is growing evidence that group consultations also help with many other long term conditions and that they can be used in the virtual space. (for further information see groupconsultations.com)

Click Here for a Guide to Group Consultations

Click Here for a guide through the common pitfalls of introducing Group Consultations

Patient Activation Measures (PAM)

PAM is a tool that allows for assessment of people’s knowledge, skills and confidence to manage their health. Research has shown that people who have greater knowledge, skills and confidence are more likely to engage in positive health behaviours and to have better health outcomes23. Use of PAM can help to target interventions to support lifestyle change that appropriate to people’s needs.

Intensive Lifestyle Medicine Programmes

Intensive Lifestyle Medicine Programmes, usually called Intensive Therapeutic Lifestyle Change (ITLC) Programmes, encourage and support drastic changes in people’s daily routine in order to improve, and sometimes reverse, chronic disease (1). Intensive Therapeutic Lifestyle Change (ITLC) Programmes are concentrated behaviour change plans that support people in making big changes in their lifestyles in a short period of time with the aim of improving, or even and reversing, their chronic conditions. They are evidence-based and cover changes in several lifestyle medicine pillars.

Currently, ITLC programs are being offered throughout the US to people with chronic health conditions. ITLC should meet the following criteria (1):

1. Evidence-based – Use approaches shown to work using accepted research methods (2-7).

2. Multimodal – Include changes in several lifestyle medicine pillars such as nutrition, physical activity, stress management and social support.

3. Multiple sessions over a short period of time – From 8 to 20 sessions, of at least 60 minutes per session, delivered at least weekly, and no shorter than 10 days for all sessions to occur.

4. Measurement of health outcomes – Specific health outcome metrics are measured, usually before and after the intervention.

One example of an American programme supported by evidence (2-7) is the Complete Health Improvement Program (CHIP):

Initially called Coronary Health Improvement Project, which started as a voluntary based project to improve coronary heart disease. However, due to the improvement of other chronic diseases, in 2012 it was renamed as Complete Health Improvement Program. Watch this video to learn about the benefits of the program. https://youtu.be/PSzXeKfxNbk

It is an intensive lifestyle intervention program delivered over a 4- to 12- week time frame in a live or online group setting. It is focused on the six pillars of lifestyle medicine:

- Nutrition – a whole food plant-predominant diet focused on “food as grown”

- Physical activity

- Sleep

- Risky substances

- Social connection

- Stress management

Since 2019, the CHIP programme is available in the UK through Compass Lifestyle Medicine (8) and it offers an online version of the program to members fo the public and it is currently being piloted in the NHS (9).

References:

- Mechley AR, Dysinger W (2015) Intensive Therapeutic Lifestyle Change Programs: A Progressive Way to Successfully Manage Health Care. Am J Lifestyle Med; 9(5) https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1559827615592344

- Ornish D, Scherwitz LW, Billings JH et al (1998) Intensive lifestyle changes for reversal of coronary heart disease. JAMA;280(23):2001-2007 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/188274

- Ornish D, Brown SE, Scherwitz LW et al (1990) Can lifestyle changes reverse coronary heart disease? The Lifestyle Heart Trial. Lancet; 336(8708):129-133 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1973470/

- Rankin P, Morton DP, Diehl H, et al (2012) Effectiveness of a volunteer-delivered lifestyle modification program for reducing cardiovascular disease risk factors. Am J Cardiol;109(1):82-86 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.07.069

- Diehl HA. Coronary risk reduction through intensive community-based lifestyle intervention: the Coronary Health Improvement Project (CHIP) experience. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82(10b):83t-87t https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9860383/

- Barnard RJ, Lattimore L, Holly RG et al (1982) Response of non-insulin-dependent diabetic patients to an intensive program of diet and exercise. Diabetes Care;5(4):370-374 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7151652/

- Racette SB, Park LK, Rashdi ST et al (2022) Benefits of the first Pritikin outpatient intensive cardiac rehabilitation program. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev;42(6):449-455 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9643589/

- Compass Lifestyle Medicine. https://compasslifestylemedicine.org.uk/about-us/

- Compass Lifestyle Medicine. CHIP in the NHS. https://compasslifestylemedicine.org.uk/chip-in-the-nhs/

This assessment is designed for clinicians to give to / talk through with your patient, to focus on what matters most to them currently and which areas of your lifestyle they might want to focus on. The answers are just a guide to where you might like to start the discussion in a lifestyle medicine consultation.

Click here to download the Print Lifestyle Screening Tool

Click here to download a more graphically simple Print Lifestyle Screening Tool

Click here to download a note taking sheet for the six pillars

Lifestyle Medicine Core Accreditation

Join BSLM as a member

Any use of this document should be done with consideration that any personal data received and stored should be done so within GDPR principles and BSLM have no involvement in the way in which this tool is utilised by Members in this regard

References

- 1Kelly MP, Barker M. Why is changing health-related behaviour so difficult? Public Health. 2016, 136, 109-116.

- 2Melvyn Hillsdon et al, Advising people to take more exercise is ineffective: a randomized controlled trial of physical activity promotion in primary care, International Journal of Epidemiology, 2002, 31, 4, 808–815

- 3Rubak S et al, Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract, (2005), 55, 305. McGinnis J et al, The Case for More Active Policy Attention to Health Promotion, Health Affairs, (2002), 21, 2

- 4McGinnis J et al, The Case for More Active Policy Attention to Health Promotion, Health Affairs, (2002), 21, 2

- 5https://www.personalisedcareinstitute.org.uk/

- 6Ahmad N et al, Person-centred care: from ideas to action, The Health Foundation, (2014)

- 1. Lenz, A. S., Rosenbaum, L., & Sheperis, D. (2016). Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of motivational enhancement therapy for reducing substance use. Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling, 37(2), 66-86.

- Lundahl, B., Moleni, T., Burke, B. L., Butters, R., Tollefson, D., Butler, C., & Rollnick, S. (2013). Motivational interviewing in medical care settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Patient Education and Counseling, 93(2), 157-168.

- Morton, K., Beauchamp, M., Prothero, A., Joyce, L., Saunders, L., Spencer-Bowdage, S., . . . Pedlar, C. (2015). The effectiveness of motivational interviewing for health behaviour change in primary care settings: A systematic review. Health Psychology Review, 9(2), 205-223.

- VanBuskirk, K. A., & Wetherell, J. L. (2014). Motivational interviewing with primary care populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 37(4), 768-780.

- Spencer, J. C., & Wheeler, S. B. (2016). A systematic review of motivational interviewing interventions in cancer patients and survivors. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(7), 1099-1105.

- Alperstein, D., & Sharpe, L. (2016). The efficacy of motivational interviewing in adults with chronic pain: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Journal of Pain, 17(4), 393-403.

- Ekong, G., & Kavookjian, J. (2016). Motivational interviewing and outcomes in adults with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(6), 944-952.

- Ghizzardi, G., Arrigoni, C., Dellafiore, F., Vellone, E., & Caruso, R. (2021 in press). Efficacy of motivational interviewing on enhancing self-care behaviors among patients with chronic heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Heart Failure Reviews.

- Ren, Y., Yang, H., Browning, C., Thomas, S., & Liu, M. (2014). Therapeutic effects of motivational interviewing on blood pressure control: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials International Journal of Cardiology, 172(2), 509-511.

- Stallings, D. T., & Schneider, J. K. (2018). Motivational interviewing and fat consumption in older adults: A meta-analysis. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 44(11), 33-43.

- Rapoport, L. et al. Evaluation of a modified cognitive–behavioural programme for weight management. Int J Obes, (2000). 24, 1726–1737

- Uchendu C and Blake H, Effectiveness of cognitive-behaviour therapy on glycaemic control and psychological outcomes in adults with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials, Diabetic Medicine, (2017), 34, 3, 328-339

- Grant AM, Stober D: Introduction. Evidence based coaching handbook. Edited by: Grant AM, Stober D. 2006, Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 1-14.

- Ammentorp, J, et al. Can life coaching improve health outcomes? – A systematic review of intervention studies. BMC Health Serv Res, (2013),13, 428 8

- https://www.england.nhs.uk/personalisedcare/social-prescribing/

- Booth A et al, What is the evidence for the effectiveness, appropriateness and feasibility of group clinics for patients with chronic conditions? A systematic review. Health Serv Deliv Res, (2015), 3, 46

- Judith H. Hibbard and Jessica Greene, What The Evidence Shows About Patient Activation: Better Health Outcomes And Care Experiences; Fewer Data On Costs, Health Affairs (2013) 32:2, 207-214

Login

Login