Purpose and meaning are vital for our wellbeing

By Dr Richard Pile

23rd Apr, 2021

In Douglas Adams’ brilliant Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy series a supercomputer is given the task of answering the ultimate question of life, the universe and everything. The answer, it turns out, is a bit of a disappointment. It’s 42.

Humankind’s search for meaning and purpose in life has been around for as long as there have been humans – and well before there were supercomputers. It’s fundamental to who we are.

But what part does living “with purpose” play in our health and wellbeing? I’d argue it should be given just as much attention as the other lifestyle medicine pillars of sleep, movement, nutrition, stress/relaxation, harmful substance cessation and relationships.

Purpose doesn’t just make you feel happy, it has cardiovascular benefits. Having PiL is associated with reduced heart attack risk in adults with known coronary heart disease, and of stroke in older adults. It has also been shown to protect against declining brain function. These findings are generated from prospective studies designed to account for possible confounding factors. It’s association rather than causation, but it’s worth looking at.

Associations have also been found between faith and wellbeing. JAMA Internal Medicine found that regular attendance at religious services was associated with significantly lower risk of death from all causes amongst women. The study concluded that religion and spirituality may be an under-appreciated resource that physicians could explore with their patients as appropriate. Systematic reviews of mortality comparing standard health interventions with religiosity and spirituality have found a positive correlation that was better than over half of the standard interventions and probably the equivalent of eating the recommended daily intake of fruit and veg, or taking a statin.

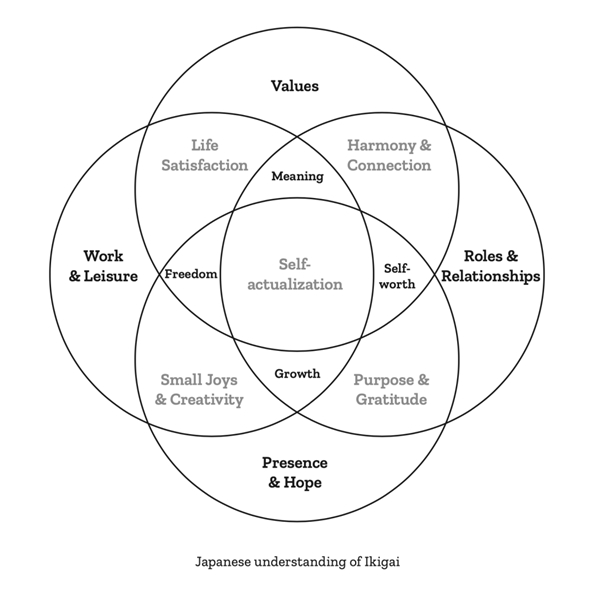

Of course, purpose and meaning don’t need to be derived from any particular faith, or indeed any faith at all. We all have values and ways of living, whether we realise it or not. A concept that I like to discuss with my patients and colleagues is that of ikigai, a Japanese word which translates roughly as “reason for being”.

You’ve probably seen images on the internet with four interlocking circles with labels such as ‘what you are good at’, ‘what you are passionate about’, ‘what the world needs’, and ‘what you can be paid for’.

Tick all four boxes and you have achieved ikigai! In fact, this is a westernised, work-based interpretation of the original concept which (according to Nicolas Kemp and Professor Akihiro Hasegawa), should look more like this

You may also be familiar with the concept of Blue Zones: the term used to describe parts of the world where there are populations of people that have unusual longevity, for example Okinawa, Japan.

So what do these areas have in common? Studies have found that people in these places have a stronger sense of purpose because life is not just about looking inward and serving themselves but also serving their communities. Older people are more active, valued and contribute to the lives of those around them.

So how do we address this, to make our lives as fulfilling as possible and to help those we advise and support? Firstly, we need to consider and imagine what our purpose may be. Then, just as we would make a plan to achieve any wellbeing-related goal, we need to consider how we can realise this purpose.

We may have more than one. We will not all have the same one. It may change as we journey through life, depending on our circumstances. If you are a lifestyle medicine practitioner, or you aspire to be, I recommend you prioritise doing this for yourself first before introducing the idea to patients.

So how do I use this in clinical practice? A recent hour-long consultation with a client is a good example. First, we went through the objective data provided by monitoring their heart rate variability, before considering what it would mean to them to be living life better. We talked about movement, nutrition and their underlying health issues.

Then we spent the last 10 minutes of the hour discussing their purpose in life. While the other 50 minutes of the discussion was helpful, it was in this last part that their eyes lit up as they realised what was most important to them.

It wasn’t ultimately about hitting 10,000 steps a day or improving their HbA1c (although these were parts of the plan), but how they were going to live the rest of their life with purpose.

Ultimately, there isn’t one neat answer to life the universe and everything; PiL will vary from person to person. But if we really want to do our best for ourselves and our patients, then we should not be afraid to ask the big questions and talk about purpose. Hopefully the answer won’t be 42!

Richard Pile has been a GP for more than 20 years including 10 years specialising in cardiovascular and lifestyle medicine and providing clinical advice on wellbeing and ill health prevention. He lives in St Albans in Hertfordshire.

Login

Login