Physical Activity

Physical inactivity is a significant cause of chronic disease. Globally, it is estimated to kill more than five million people every year. The World Health Organisation has identified physical inactivity as the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality. Inactive lifestyles are also a proven risk factor in a range of chronic health conditions including heart attacks, strokes, type 2 diabetes and depression.

Our daily energy expenditure from physical activity has been dropping dramatically, in the developed world at least, since the 1950s . Increasing use of motor vehicles, labour saving devices and the more recent growth in “time- wasting technology” such as mobile devices, games consoles, home computers and the internet has made us less physically active and increasingly sedentary.

The British Society of Lifestyle Medicine prioritises the importance of physical activity as one of the six pillars of lifestyle medicine. Regular exercise can help us live longer, reduce periods of ill health in our lives and increase the all-important “healthspan”.

For clinicians who practice lifestyle medicine, a priority should be supporting people to choose ways they can incorporate more physical activity into their daily lives. Sometimes just supporting people to reduce the time spent sitting down can make a big difference – it isn’t about convincing all of our patients to become marathon runners!

For lifestyle medicine practitioners, it is important to have a solid understanding of the evidence-base that supports the case for increased physical activity. Utilising this understanding effectively allows us to best support our patients.

Being more active can help to prevent a range of illnesses but it can also play a part in treatment. Physical activity can lower the risk of developing a range of chronic health conditions including heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes and even certain types of cancer. It has also been shown to reduce the risk of frailty in old age .

A study by Steven Blair of the University of the University of South Carolina in 2009 stated that, “the evidence supports the conclusion that physical inactivity is one of the most important public health problems of the 21st century, and may even be the most important.”

He added: “There is now overwhelming evidence that regular physical activity has important and wide-ranging health benefits. These range from reduced risk of chronic diseases such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and some cancers to enhanced function and preservation of function with age.”

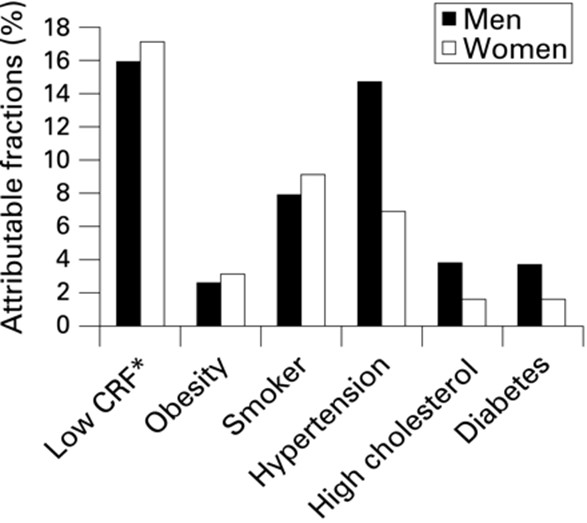

The study looked at a range of ‘attributable fractions’, including physical fitness levels, and their contribution to avoidable deaths. Attributable fractions are estimates of the number of deaths in a population that would have been avoided if a specific risk factor had been absent

It concluded that low cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) was an attributable fraction in 16% of deaths – see figure 1 – more than diabetes, obesity and smoking combined.

Figure 1: Blair S (2009) Physical Inactivity: the biggest public health problem of the 21st century. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2009;43:1-2

There are also mental health benefits to physical activity with studies showing that being active can have a positive impact on brain health and cognition and reduce the risk from dementia. It can also help to reduce stress, improve anxiety & depression – and can help us to sleep better. Physical activity is also a powerful tool to help us address the underlying issue of obesity, which is a factor in many chronic health conditions.

In addition to the above evidence, it is also crucial to have a deep understanding of the proven techniques for encouraging people to be more physically active. Lifestyle always starts with the individual – and this person-centred approach should reflect and acknowledge each person’s unique challenges, circumstances and capabilities. This is hugely important if we are to find effective strategies for promoting physical activity.

Here, BSLM supports the use of behaviour change techniques such as motivational interviewing, readiness assessments and goal setting. It is important to start where patients are and find non-judgemental ways to break down some of the barriers people may face to being active.

Login

Login