Obesity and Lifestyle Medicine; The Future Choices Report

By Dr Ellen Fallows

4th Dec, 2020

The Future Choices report was commissioned by the UK government’s Chief Scientific Adviser to answer the question “how can we deliver a sustainable response to obesity over the next 40 years?” It is a fantastically rich document. In short, it suggests that obesity isn’t an issue of personal will power over eating too much and moving too little, but a very complex problem that ultimately, government and society should protect its citizens from, particularly those most vulnerable such as children.

How significant is the problem?

Very – with current trends the majority of adults will be obese by 2050 and this has huge economic and health costs.

Obesity was compared with the scale and complexity of the issue of global warming.

Where is obesity most often found?

In the North of England, Amongst more deprived populations and certain ethnic groups such as Bangladeshi populations.

What do they think causes obesity?

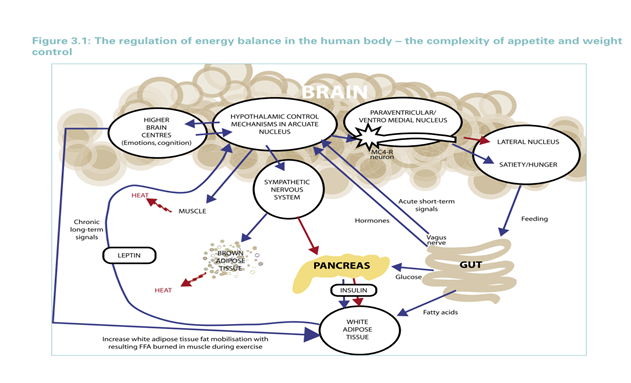

The report concludes that obesity doesn’t arise out of dysregulation of energy expenditure (which is relatively similar from person to person and if anything is increased in the obese as their Basal Metabolic Rate rises) but out of the neuroendocrine processes that regulate energy intake. These complex biological processes regulating energy intake tend to preserve sufficient body weight rather than prevent excess body weight (they provide an excellent summary diagram, see below). These processes interact with several social and environmental factors. The conclusion being that “most obesity in the modern world is a natural biological response to a changed environment and innate body-weight regulatory mechanisms have been overwhelmed by energy-dense diets and sedentary lifestyles.” (Prentice A, 2007) It has been suggested that this does not rule out pharmacological solutions to obesity for example in agents that suppress appetite. However, they state that evidence suggests that “physiological difference between people are not the root cause of obesity”.

They review the evidence for behavioural interventions

The conclusion is the evidence is in its infancy, but important themes emerge:

- Beliefs are important

- Habits play a part

- Barriers include inability to translate intention into action

- Sometimes people’s automatic attitudes are not apparent

- The “moral climate” affects people’s desire to make changes

- The living environment has a large role to play including opportunities to be active and the availability of food

- The price of food has gone down for processed food, whereas fresh fruit and veg prices have gone up

- Longer working hours are associated with obesity

- Technology has variable impact – it may help people to lose weight and it may increase the chance of obesity

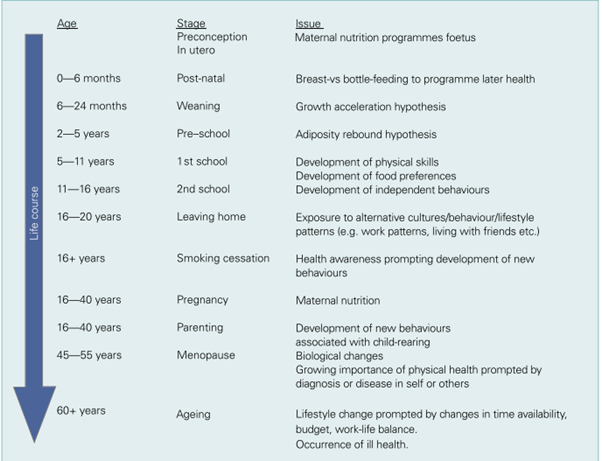

Which time points in our lifespan appear to be critical?

They suggest there is no one point but multiple points at which intervention might be successful but there is evidence to suggest that people are more susceptible to behavioural change at certain times of their life.

Why haven’t we found a solution yet?

Parallels have been drawn with the difficulties of the huge task of addressing climate change. They suggest that such a huge and complex issue has caused “policy cacophony” and uncertainty over where to focus resources. The environmental determinants have been misunderstood and under researched whilst policy “drifts towards individualised responsibility”. Similarly, they think, we all recognise the need to act but we all feel “powerless or uncertain about how to act”.

Their chapter on complexity lays out the challenge. They group the systems influencing obesity into “thematic clusters” which are all interconnected. These clusters are:

- physiology

- individual activity

- physical environment

- food consumption

- food production

- individual psychology

- social psychology

Has anyone found anything that might work?

Not really, but there are pockets of good practice.

For example, they quote the North Karelia Project in Finland:

The aim was to reduce heart disease. It started in 1970 and ran over 20 years. It was a community programme looking at “community lifestyle” including physical activity, weight, diabetes, alcohol, psychosocial factors, diet and smoking. It used multiple different approaches such as medica, meetings, local health service measures, environmental changes such as collaborations with food manufacturers and promotion of vegetable growing. Results were that coronary heart disease deaths dropped by 59% in men.

Having given an example of a comprehensive lifestyle change community programme they then analyse the attempts in the UK to focus on single issue campaigns such as smoking cessation, alcohol reduction, some of which have had success in these specific areas.

What do they think we need to do?

Firstly, they suggest we recognise we’re all in this together given we have an “inherent human predisposition to gain weight in a world of abundant energy-dense food and drink in conditions of reducing levels of physical activity”. This means we need to move away from the assumption that an individual’s weight is a matter solely of personal responsibility or individual choice. So, we need to ask, “fundamental questions about how we live our lives and create a comprehensive, long-term strategy to address the problems”. Secondly, we need to create environmental and social changes that favour healthy behaviours.

Specifically, they suggest:

- we should offer treatment for obesity on the NHS and all be trained to manage those with obesity

- we need multiple interventions to prevent obesity

- we need all policy areas to reflect the need to prevent and treat obesity

These actions should be based around some core principles:

- Use of system-wide approaches

- Prioritisation of ill-health prevention

- Engagement of a wide range of stakeholders

- Use of long-term interventions

- Continuous evaluation of interventions

They end suggesting a paradigm shift

The authors finish by suggesting that obesity challenges traditional research paradigms given the urgency of the situation. They suggest we get on with the “best evidence available” and focus on “practice-based evidence” which might need changes in existing research funding and training coupled with leadership, vision and sustained commitment.

What does this mean for lifestyle medicine?

It is very telling that the successful example for obesity management involved a comprehensive lifestyle intervention – a key part of the lifestyle medicine approach. This report is a superb review of the situation we find ourselves in, the challenges we face and where we need to go to seek solutions. It strengthens the mandate for lifestyle medicine – we are one part of this new paradigm – one that can set out the vision for what role health care professionals can play in this new approach that complements the policy changes that will be needed.

Dr Ellen Fallows

References

Butland B et al, Foresight, Tackling Obesities: Future Choices – Project Report, 2nd Edition, Government Office for Science https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/reducing-obesity-future-choices

Prentice, A. (2007), Are defects in energy expenditure involved in the causation of obesity?. Obesity Reviews, 8: 89-91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00325.x

Login

Login