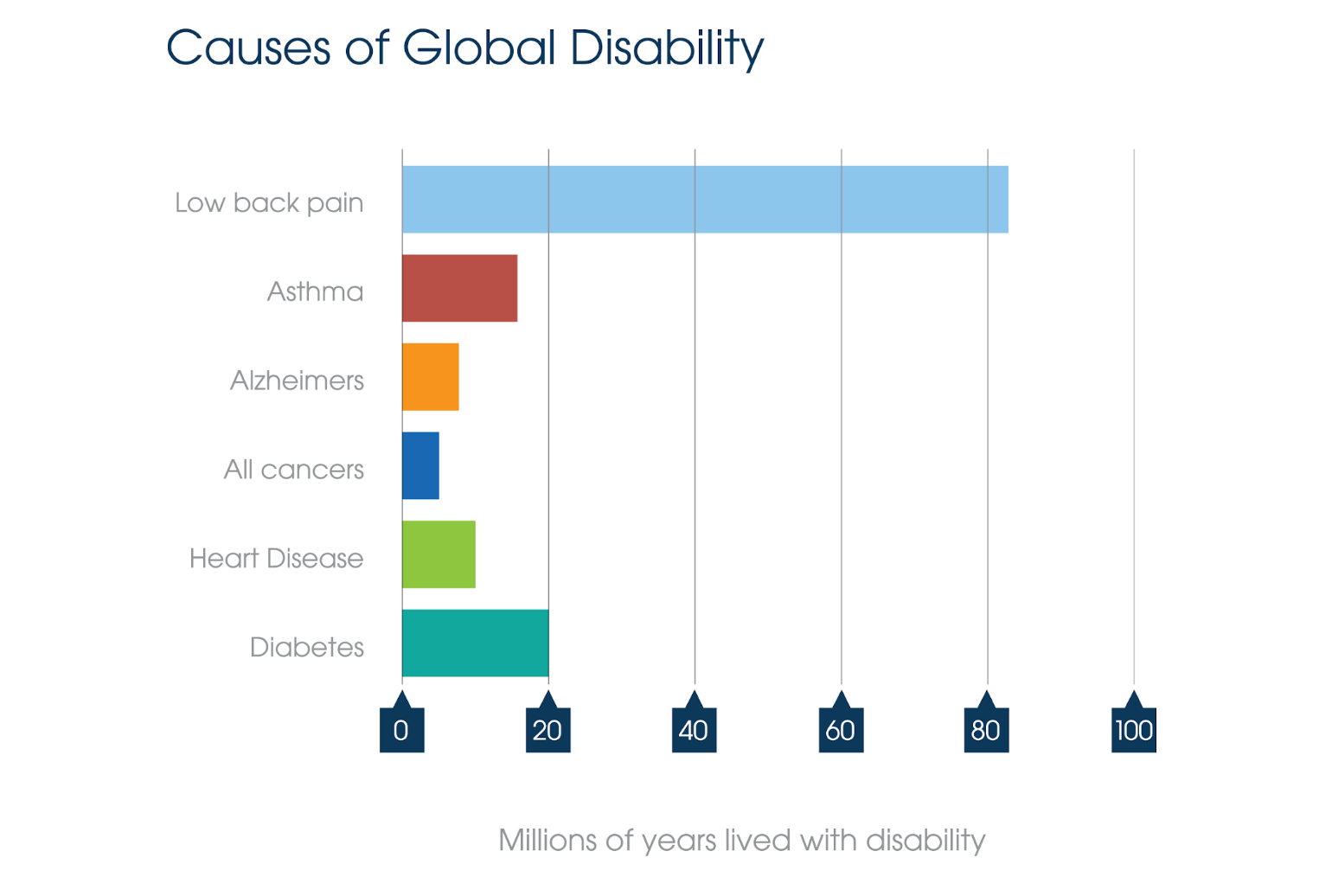

“Lower back pain (LBP) is not a disease, and yet LBP causes more disability than Alzheimers, Asthma, All Cancers, Diabetes and Heart Disease combined”1

– (Hoy et al, 2014).

Question:

Why does it cause so much disability (which is different to pain)?

Answer:

We have medicalised what is essentially a symptom.

Before I develop my argument, let me start by saying that obviously, medicine has achieved tremendous things… Antibiotics, organ replacement, vaccinations, heart valve replacements… The list is extensive.

But it has made a right mess of lower back pain.

Ask family doctors who their heart-sink patients are, and you’ll soon hear the words “lower back pain”. And the inappropriate prescription of opiates for back pain is a medical calamity.

Let’s come back to the statement that lower back pain is a symptom.

What is a symptom? Put simply, a symptom is what someone feels to be abnormal. But the dictionaries have conflated the definition to be “any feeling of illness or physical or mental change that is caused by a particular disease”. My definition, and the one I was taught over 30 years ago did not require the use of the word “disease” or “pathology”. It seems to me that nowadays the presence of a symptom implies the presence of disease – at least from the above textbook definition.

But of course, it doesn’t. I might have a headache. Does that mean I have a disease? If I have a cough, do I have a disease? Not necessarily. So, if I have lower back pain, do I have a disease? Probably not – there’s roughly a 99% probability that I don’t, according to the research2 (Henschke et al, 2009).

Headache, cough, lower back pain – these are all symptoms. They may or may not be indications of underlying disease.

So, if lower back pain is not a disease/pathology, why do we treat it as though it were? With medications, expensive investigations, scary sounding diagnoses, injections, and so on…

A recent article in the British Medical Journal 3 (Kuhlein et al, 2023) highlighted the current unfortunate tendency to over-diagnose and prescribe too much medicine. I think lower back pain is a case-in-point.

What happens when we classify something as a medical disorder? We have to find medical solutions. There have been clinical guidelines in place in the UK and other countries for the management of lower back pain for as long as I have been a practising osteopath (over 30 years).

Reviewing the guidelines, there are few strong recommendations, other than the list of “Don’ts”. So, there’s little evidence that much of what medicine – including complementary medicine – has to offer actually does much good.

And is the impact of lower back pain decreasing as we have tried to adhere to those guidelines? No. There are more people disabled by lower back pain in the world now than 20 years ago 4 (GBD 2021), and – with an aging and less active population (physical inactivity rocketed during the pandemic) – it’s projected to get worse. Why?

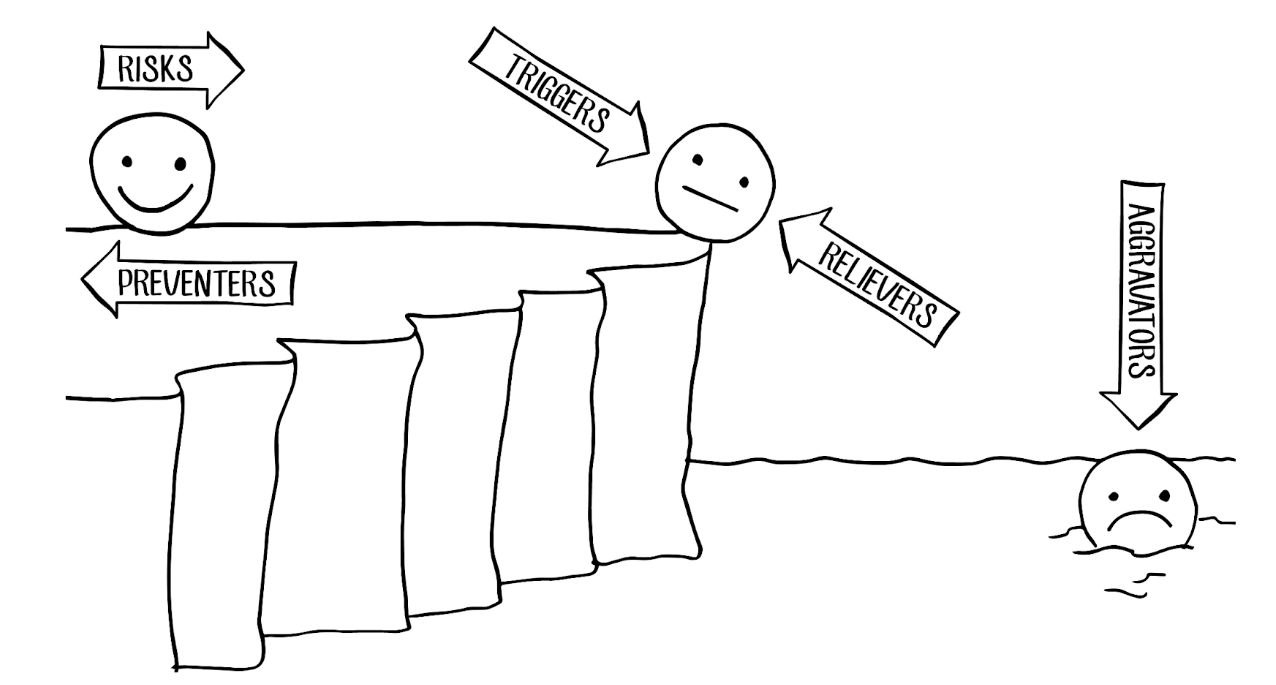

Because lower back pain is not a medical problem. It’s a lifestyle problem. Up until now, all medicine (and complementary medicine) has typically offered are what I call “Relievers”. And as you’ll see from The Cliff of PainTM image below, they only help the sufferer to regain the Cliff Top.

Having reached the Cliff Top, people imagine that they are “fixed”. But studies can show as many as 69% of first time lower back pain sufferers will have a relapse within a year 5 (Da Silva et al, 2019) It is only by reducing the Risk factors that you can get right back from the edge. This is not a medical solution. It’s a lifestyle solution.

De-medicalising lower back pain…

The evidence is that education and exercise are the most important and effective interventions for chronic LBP sufferers. These are NOT medical interventions. They are good old listening, talking and moving.

We deliver this solution online, within a group consultation style of coaching-based intervention.

Using The Cliff of PainTM metaphor, we help patients to identify their Aggravators and Triggers and coach them to work out how they can modify these, while using whichever evidence-based Relievers they like in order to regain the Cliff Top. But – more importantly – we also help them to identify their Risks, and again, coach them towards modifying or reducing these. Following graded exposure principles, we coach them to reintroduce feared activities.

This is an 8 week program, with 2 sessions each week – one focused on education, discussion and coaching and the other on exercise, graded exposure and coaching. We use a coaching app to support the patients 24/7, nudging them to stay on track, and providing group accountability to maximise behaviour change. Fear is a big issue for many chronic LBP sufferers, so having a direct line to a clinician is very reassuring.

It is grounded in Jensen’s Model of Pain Self-management 6 (Day et al, 2014), and might be described as a mindfulness based intervention in a group setting.

We have to do something very different for the millions of LBP sufferers. Coaching them towards prevention has to be the way ahead.

If you’d like to learn more, (especially if you could access funding to study the effectiveness of this intervention) please get in touch with gavin@active-x.co.uk

Sources

- Hoy, D., March, L., Brooks, P., Blyth, F., Woolf, A., Bain, C., Williams, G., Smith, E., Vos, T., Barendregt, J., Murray, C., Burstein, R., Buchbinder, R., 2014. The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis annrheumdis–2013–204428.

- Henschke, N., Maher, C.G., Refshauge, K.M., Herbert, R.D., Cumming, R.G., Bleasel, J., York, J., Das, A. and McAuley, J.H. (2009), Prevalence of and screening for serious spinal pathology in patients presenting to primary care settings with acute low back pain. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 60: 3072-3080. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.24853

- Kuhlein T, Macdonald H, Kramer B, Johansson M, Woloshin S, McCaffery K et al. Overdiagnosis and too much medicine in a world of crises BMJ 2023; 382 :p1865 doi:10.1136/bmj.p1865

- GBD 2021 Low Back Pain Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of low back pain, 1990-2020, its attributable risk factors, and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023 May 22;5(6):e316-e329. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(23)00098-X. PMID: 37273833; PMCID: PMC10234592.

- Da Silva T, Mills K, Brown BT, Pocovi N, De Campos T, Maher C, Hancock MJ,

Recurrence of low back pain is common: a prospective inception cohort study,

Journal of Physiotherapy, Volume 65, Issue 3,2019,Pages 159-165,ISSN 1836-9553, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2019.04.010. Accessed: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1836955319300591

- Day MA, Jensen MP, Ehde DM, Thorn BE, Toward a Theoretical Model for Mindfulness-Based Pain Management, The Journal of Pain,Volume 15, Issue 7, 2014, Pages 691-703, ISSN 1526-5900, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2014.03.003. Accessed: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1526590014006725

Login

Login