BSLM Consensus Statement: Anti-Obesity Medications

By The British Society of Lifestyle Medicine (BSLM), The British Association for Nutrition and Lifestyle Medicine (BANT) and the College of Medicine and Integrated Health (CoM). March 2025.

3rd Mar, 2025

We urge policy makers, health care leaders and regulatory bodies to ensure that anti-obesity medications (AOMs) are used safely, effectively and sustainably.

We call for resources for policy and public health to be prioritised over medication-based approaches, which when used, must be supported by a Lifestyle Medicine wrap-around service to protect our most vulnerable individuals from unintended harms and to achieve sustainable weight loss that improves health outcomes.

We recommend a cautious roll-out of these new medicines with more real-world data to inform safer practice.

AOMs such as the GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and dual GLP-1/GIP agents have emerged as effective treatments for obesity. Whilst there is an urgent need to improve care for people with obesity, particularly to address stigmatising beliefs around the condition, we are concerned that the planned roll-out of AOMs may not be safe, effective or sustainable for the following reasons:

- An over-focus on AOMs risks distracting public health efforts to tackle the root causes of obesity, namely poverty1 and a broken food system2. This approach could also risk an arms race between pharmaceuticals designed to reduce appetite and the food industry creating food to over-ride natural satiety mechanisms3.

- Restricting appetite through AOMs without individually tailored wraparound support, risks unintended harms such as worsening malnutrition (including muscle wasting/sarcopenia) for the most vulnerable. People with obesity, particularly those facing food insecurity, already have high rates of vitamin and mineral deficiencies4 which can be exacerbated by restrictive food intake.

- There are significant workload implications for primary care teams particularly with insufficient wraparound support.5 Primary care is already facing significant pressure from the increase rates of chronic disease, reductions in funding, a shift of care into community and a need to deliver preventive care.

Background

The British Society of Lifestyle Medicine (BSLM) is a UK educational charity that provides clinicians from all backgrounds with the wider knowledge and skills needed to address the root causes of obesity. The College of Medicine and Integrated Health advocates for a multi-faceted approach to healthcare beyond pills. The British Association for Nutrition and Lifestyle Medicine is the leading professional body for Registered Nutritional Therapy Practitioners and BANT Registered Nutritionists®.

The BSLM Learning Academy provides training and qualifications for clinicians to provide the holistic, wraparound care that is urgently required to ensure that AOMs are safe, effective, equitable and sustainable.

The publication of the NICE guideline on overweight and obesity management6 on 14 January 2025, allows for Tirzepatide prescribing more widely through primary care. A funding variation has been proposed (details expected to be published in March 2025) to prioritise prescribing of Tirzepatide to particular groups of patients. These developments necessitate improved training of clinicians and provision of wraparound services to support safe and effective use of AOMs.

Anti-Obesity Medications (AOM)

AOMs include synthetic Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) Receptor Agonists such as Liraglutide, Dulaglutide, Semaglatide and relatively newer black-label, dual GLP1/glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) Receptor Agonist, Tirzepatide. Use of AOMs in trials has shown:

-

· an average of 10-25% or more body weight reduction7 , 8

· reductions in average blood sugar, reduced cardiovascular risk and in some cases remission of Type 2 Diabetes9

· appetite suppression resulting in reduced caloric intake and reduction of food cravings10

· emerging evidence for a reduction in cravings for other harmful substances such as alcohol and smoking11

· emerging evidence for an anti-inflammatory effect12

The Role of Lifestyle Medicine in Obesity Care

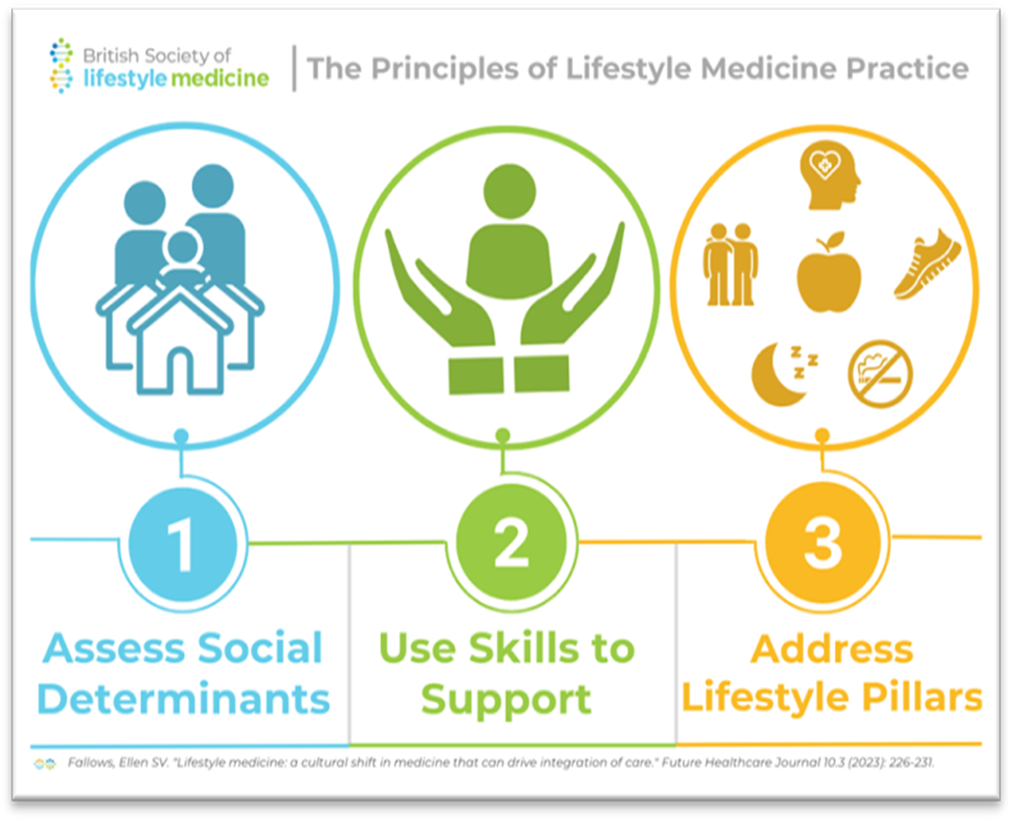

Lifestyle Medicine is built on three principles (see below graphic) – acknowledging the need for assessment and action on the socioeconomic determinants of health; using proven skills to support people to make and sustain changes around the six pillars of lifestyle medicine – supporting mental wellbeing, maintaining healthy relationships, improving nutritional quality, sleep quality and increasing physical activity whilst minimising exposure to harmful substances.13

Using a Lifestyle Medicine approach to long-term conditions such as obesity can:14 , 15

- Promote sustainable weight loss through behaviour change

- Support improvements in the quality of food to reduce the risk of malnutrition

- Address the wider drivers of obesity including stress, social isolation, poor mental wellbeing, inactivity, sedentary behaviour and poor-quality sleep

- Improve metabolic markers, including blood pressure, lipid profiles and blood sugar control

- Enhance psychological wellbeing and quality of life

Unintended harms of AOM use

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends the use of AOMs in conjunction with a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity. However, these guidelines fail to emphasise the need for support around nutritional quality, over and above caloric restriction. These risks failing to address “malnutrition in obesity”16 which can be exacerbated through caloric restriction without support for nutritional quality.

Serious adverse effects from AOM use without adequate Lifestyle Medicine wraparound care, include malnutrition, with or without sarcopenia (muscle loss). Severe and prolonged caloric restriction can result in unintended adverse health outcomes including symptomatic protein, vitamin and mineral deficiencies. For example, there have been case reports of severe thiamine deficiency resulting from malnutrition whilst using Semaglutide that resulted in Wernicke’s Encephalopathy which can cause an irreversible dementia syndrome.17 , 18

Similarly, without sufficient support for adequate protein intake and resistance training, AOMs have been associated with fat-free mass loss of 25-39% over 36-72 weeks.19 Loss of fat-free mass represents in part, muscle mass loss, when muscle mass is known to be critical for health and longevity.20 The health risks of severe caloric restriction have been studied in historical research of enforced dietary restriction and include muscle weakness, reduced aerobic exercise capacity, painful limb oedema and poor mental health.21

Nutritional assessment prior to prescribing, during and after use of AOMs along with adequate support for resistance training and physical activity is needed to avoid these unintended harms and ensure that weight loss results in improved health outcomes.

AOM prescribing should be part of a weight management approach led by trained Lifestyle Medicine practitioners, who bring expertise in nutrition, physical activity (including strength training), mental wellbeing, stress reduction and interventions to improve sleep quality and can refer onwards when more complex cases require dietetics or specialist intervention.

Safe, effective and sustainable AOM use requires Lifestyle Medicine Wraparound Care

Lifestyle Medicine wraparound care includes:

- assessing nutritional state before, during and after treatment

- assessing the drivers of obesity in an individualised and holistic way covering sleep quality, physical activity, sedentary behaviour, harmful substances (smoking/alcohol/drugs/prescribed medicines that cause weight gain), social isolation, mental wellbeing and nutrition

- creating a person-centred care plan that asks, “what matters most to you right now about your health?”

- creating an individualised and supported plan that draws on available community support and the wider primary care multi-disciplinary team that can include nurses, pharmacists, dietitians, health coaches, mental health workers and social prescribing link workers

- a personalised follow-up plan including a plan for medication down-titration as required following rapid weight loss e.g. how to monitor blood sugar, blood pressure, side effects of medications affected by weight loss such as blood sugar lowering medicines, lithium, anti-coagulants, anti-hypertensives, anti-psychotics

Without this wraparound care, AOM use risks worsening pre-existing malnutrition, worsening inequity (as those facing food poverty will likely only be able to reduce the amount of poor-quality food eaten thus remain at risk of malnutrition) and failing to address the root causes of obesity. This will result in AOM use that is unlikely to be sustainable and for individuals weight loss that may not be sustained once medications are stopped.

View the BSLM Webinar on this Topic

References

- Autret, Kristen, and Traci A. Bekelman. “Socioeconomic status and obesity.” Journal of the Endocrine Society 8.11 (2024): bvae176.

- The National Food Strategy – The Plan

- Fallows, Ellen, Louisa Ells, and Varun Anand. “Semaglutide and the future of obesity care in the UK.” The Lancet 401.10394 (2023): 2093-2096.

- Aasheim ET. Vitamin status in morbidly obese patients: a cross-sectional study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:362–369.

- Mahase E. Weight loss drugs: New online pharmacy checks have “significant” GP workload implications BMJ 2025; 388 :r295 doi:10.1136/bmj.r295

- Overview | Overweight and obesity management | Guidance | NICE

- Davies, M. J., Bergenstal, R., Bode, B., et al. (2021). Efficacy of Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. The New England Journal of Medicine, 384(11), 989–1002. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2032183

- Jastreboff, A. M., Kaplan, L. M., Frías, J. P., et al. (2022). Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. The New England Journal of Medicine, 387(3), 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2206038

- Ryan, D. H., Yockey, S. R. (2017). Weight Loss and Improvement in Comorbidity: Differences at 5%, 10%, 15%, and Over. Current Obesity Reports, 6(2), 187–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-017-0262-y

- Badulescu, Sebastian, et al. “Glucagon-like peptide 1 agonist and effects on reward behaviour: a systematic review.” Physiology & Behavior (2024): 114622.

- Yammine, Luba, et al. “Cigarette smoking, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists as a potential treatment for smokers with diabetes: An integrative review.” Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 149 (2019): 78-88.

- Lee, Young-Sun, and Hee-Sook Jun. “Anti‐inflammatory effects of GLP‐1‐based therapies beyond glucose control.” Mediators of inflammation 2016.1 (2016): 3094642.

- Fallows, Ellen SV. “Lifestyle medicine: a cultural shift in medicine that can drive integration of care.” Future Healthcare Journal 10.3 (2023): 226-231.

- Kushner, Robert F., and Kirsten Webb Sorensen. “Lifestyle medicine: the future of chronic disease management.” Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity 20.5 (2013): 389-395.

- Wadden, T. A., Tronieri, J. S., Butryn, M. L. (2020). Lifestyle Modification Approaches for the Treatment of Obesity in Adults. The American Psychologist, 75(2), 235–251. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000517

- Barazzoni, R., Gortan Cappellari, G. Double burden of malnutrition in persons with obesity. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 21, 307–313 (2020).

- From Weight Loss to Neurological Deficits: A Case of Wernicke’s Encephalopathy Stemming From Prescription Weight Loss Medication

- Ali, Suhib Alhaj, et al. “S4686 Semaglutide’s Hidden Perils: A Rare Case of Malnutrition and Wernicke Encephalopathy.” Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology ACG 119.10S (2024): S2964

- Prado, Carla M., et al. “Muscle matters: the effects of medically induced weight loss on skeletal muscle.” The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 12.11 (2024): 785-787.

- Conte C, Hall KD, Klein S. Is Weight Loss–Induced Muscle Mass Loss Clinically Relevant? JAMA. 2024;332(1):9–10. doi:10.1001/jama.2024.6586

- Keys, Ancel, et al. “The biology of human starvation. (2 vols).” (1950).

Login

Login