Lifestyle medicine and the social determinants of health

By Dr Ellen Fallows

5th Nov, 2021

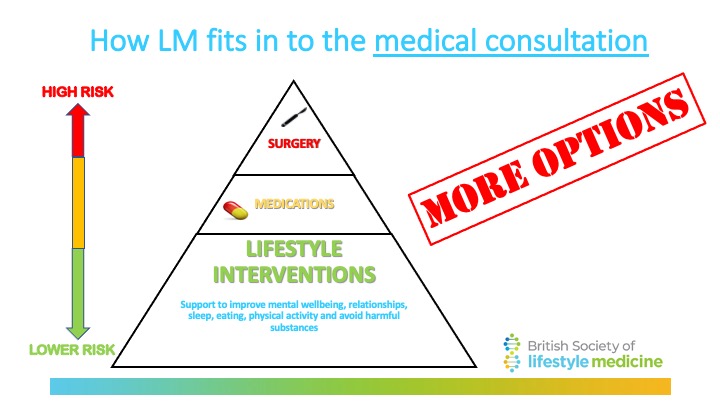

As a GP who uses lifestyle medicine in my consultations with patients, I’ve learned two very important lessons over the years. Firstly, for most lifestyle-related illnesses, medications don’t often get to the root causes of chronic conditions and may even distract us from what really needs to be done at a wider societal level. Secondly, most of my patients know what a healthy lifestyle looks like; it’s achieving it that’s the hard part.

I was fortunate to be involved in The Diamond Study at the Nuffield Department of Primary Healthcare, Oxford1; a small pilot into primary care nurse-led support for dietary change in Type-2 Diabetes. For the first time, I found my patients taking their health back into their own hands and bringing their blood sugar down through lifestyle changes. Many patients expressed frustration in never having been given this support in the past.

On reflection, years of prescribing medications and insulin had never achieved this degree of improvement; something we are now calling remission. The impact of this type of intervention should not be underestimated – Type 2 diabetes is an illness which affects 1 in 16 people in the UK, and causes almost 15% of adult deaths worldwide.

Where drugs had largely distracted me from the root causes of Type-2 Diabetes, supporting my patients to make improvements to their diet didn’t just improve their diabetes, but also their osteoarthritis, depression, obesity, hypertension and even remission of atrial fibrillation for one patient. My role was to support my nursing colleagues, validate and encourage my patient’s hard work, sign-post to additional community support and de-prescribe, over and over again; it really brought back the joy of being a GP.

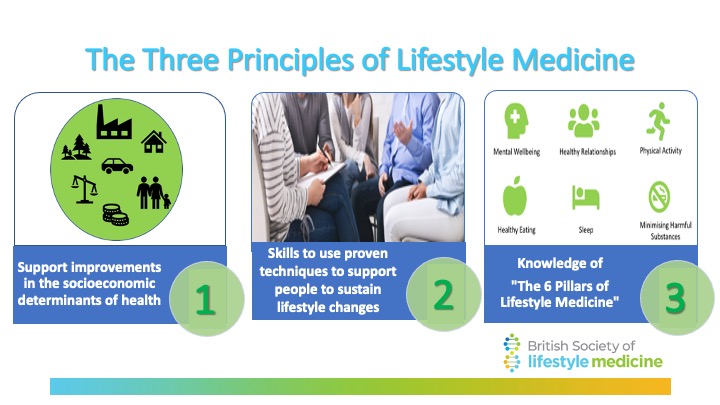

Following this pilot, I continue to work with patients supporting them with dietary change in group clinics and found that it wasn’t just food but other lifestyle issues people wanted to talk through and change. By combining dietary changes with the other lifestyle medicine pillars, depending on the patient’s priorities – mental wellbeing, healthy relationships, physical activity, sleep or avoidance of harmful substances and behaviours – we were able to have an even bigger impact.

When it comes to the root causes of many common chronic health conditions, large-scale public health and policy interventions to address the socioeconomic determinants of health are critical.

But clinicians can still acknowledge these determinants, and provide support at a one to one, or small group level, by spending more time talking to patients about what is going on in their lives; what is holding them back from making the changes they want to make, what financial pressures they are under, can they access and cook healthy food, how they are sleeping, what family and friends support do they have?

We need to resist the pressure to crowd out these issues by the management of ever-growing lists of investigations, medications and referrals. This is why the BSLM focuses on the 3 principles of Lifestyle Medicine that include addressing socioeconomic determinants of health, the skills needed to support people to sustain lifestyle changes, as well as knowledge of the 6 pillars of lifestyle medicine. (see below)

Knowing what’s healthy is not enough

Now I spend more time talking to my patients about what is going on in their lives, I’ve found that prioritising listening, talking about challenges and people’s personal goals is more effective than simple advice-giving. The most empowering interventions are the ones which help people to apply their knowledge in a way that works for them.

Supporting people to change their lifestyle and behaviour is challenging; this isn’t what people have grown to expect in their consultations, and it takes time. Patients often come ready to be “told off” and may have had negative experiences of being blamed or stigmatised; this is why continuity of care and trust are crucial – something unfortunately in short supply in busy NHS practice today.

The reality is that every patient who sits in front of us in the consultation room faces different circumstances and challenges. We therefore need to support behaviour change through person-centred techniques. This means starting our consultations with the patient agenda – asking “what matters most to you right now” and then really listening, without judgment and without blaming. This way, we can start where each person is at and build on the knowledge and skills they already have.

Reducing socio-economic barriers to lifestyle and behaviour change

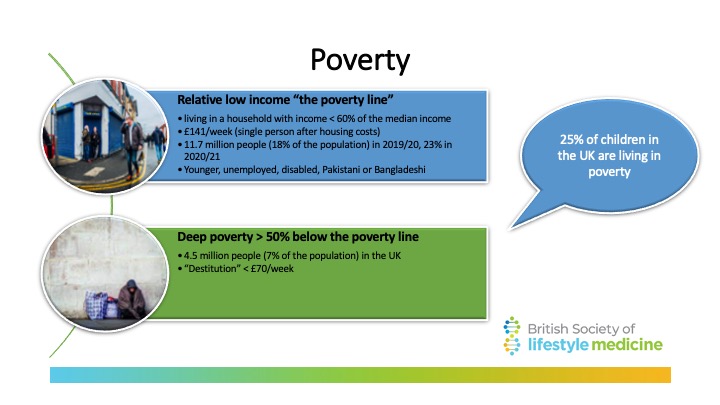

To really transform healthcare, we must support and advocate for solutions to the socio-economic determinants of health. Poverty, inequality, food insecurity, poor housing, job insecurity, a feeling of hopelessness and a lack of control are all very real problems for the 11.7 million people living on a low income in the UK. Most shocking is that nearly a quarter of UK children live below the poverty line in the UK2. This is one of the most significant barriers people face to healthy living.

As a GP, I’ve often felt powerless to affect these wider determinants of health – it feels like everything is a problem for overwhelmed primary care teams and I wonder if I would be more impactful as a local politician who might be able to increase access to green spaces, active transport or cheaper veg for example.

However, there is one thing I know I can do and that is use the position of influence I do have to raise this agenda all the time outside of my consulting room with those who can make changes. This might be in a Primary Care Network meeting with other practices, with my local council, with the wider hospital trust and Clinical Commissioning Groups and even as a voting citizen at the ballot box. I can also work with my local voluntary groups who are on the ground addressing these issues daily, I can raise my voice to locally support and protect the role of district nurses, health visitors, social workers, social prescribers, citizens advice and community groups – mentoring them, speaking up for these teams in meetings and advocating for their key role in healthcare.

Do more for those who need it most

The first thing we must do, in my view, is proceed with caution when it comes to lifestyle advice. ‘One size fits all’ lifestyle advice, which doesn’t acknowledge underlying inequalities, risks doing more harm than good. As Michael Marmot warned in his book The Health Gap: “People with little control over their lives do not feel able to make healthy choices. Which may be the reason that health advice, if effective at all, can act to increase inequalities in unhealthy behaviours.”

We have seen these inequalities play out with smoking. In the past, there wasn’t a social gradient; people from all backgrounds smoked. Now smoking is concentrated in more deprived groups. Wealthier people have been able to stop – those facing deprivation have not. As Marmot goes on, “failure to recognise the effects of inequalities risks “lifestyle drift” and “citizen shift” in UK health policy; this risks inaction locally to address socioeconomic factors and clinicians who may blame patients for their lifestyle in a consultation.

In the consulting room

So how can we do our bit in the consulting room when it comes to addressing inequalities? It starts, I believe, with using proven behavioural and social interventions to make the lifestyle support we provide smarter – and ultimately more effective. This includes social prescribing, health coaching, shared decision making, motivational interviewing and group consultations.

Secondly, care needs to be much more personalised. It needs to start with the patient in front of us and their unique circumstances, challenges and priorities. So, try that opening gambit: “What matters most to you about your health right now?”

We also need better tools to be able to identify those in our practice who may need more help. There are a few validated research tools to do this, but just asking the right questions is a good start, such as, “do you have difficulty making ends meet at the end of the month?”

The inverse care law has only worsened with Covid-19; more deprived patients are less able to reach us and the risk is, as clinicians, we may be more likely to discuss lifestyle issues with the well off. If we are really to address health inequalities, this has to change.

This may mean having to rethink some of the things we are willing to do – as GPs particularly. While many of us might be keen to dispense advice like “eat more fruit and veg” and “go for a run” how many of us believe in the health benefits of writing a letter to a patient’s landlord on their behalf to make them aware of the health impact which poor housing is having on their tenant? Or to readily offer food vouchers or engage and signpost to local community and voluntary groups who could support someone’s mental health?

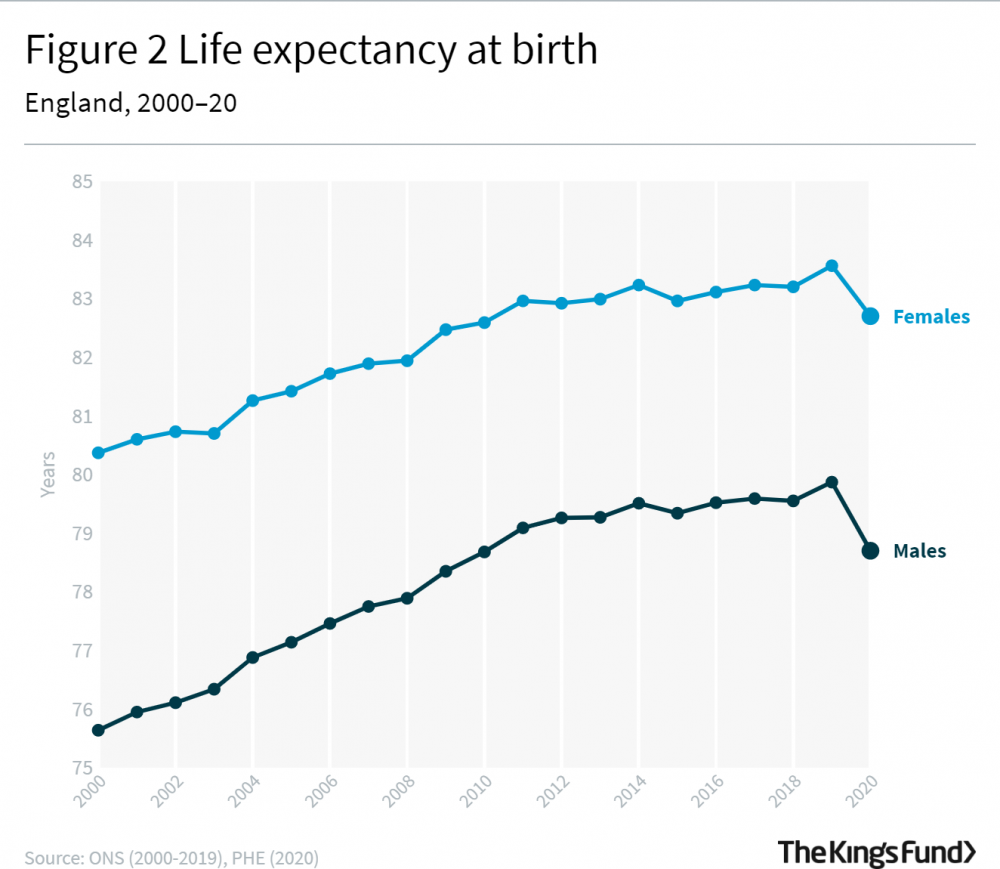

Inequalities are widening and the health implications of that are becoming starker. We know that steadily improving life expectancy has stalled since 2011 in the UK and worsening socio-economic inequality is partly to blame. As the Marmot Review “10 Years On” revealed earlier this year, the gap in life expectancy between the richest and the poorest areas has widened again in 2020: to 10 years for men and 8.5 years for women. This compared with 9.3 years and 7.9 years in 2019.

In conclusion, Marmot says: “Put simply, if health has stopped improving, then society has stopped improving. Evidence, assembled globally, shows that health is a good measure of social and economic progress. When a society is flourishing, health tends to flourish. When a society has large social and economic inequalities, it also has large inequalities in health … The health of the population is not just a matter of how well the health service is funded and functions, important as that is, but also the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age, and inequities in power, money, and resources. Taken together, these are the social determinants of health.”

It is these socio-economic determinants of health which lifestyle medicine must consider both in and outside the consulting room if it is to be truly effective.

Dr Ellen Fallows,

BSLM Learning Academy Director

- As the British Society of Lifestyle Medicine’s Learning Academy Director, I am committed to education around the 3 principles of lifestyle medicine; in particular supporting clinicians and practitioners to understand the impact of the socio-economic determinants of health. The academy will equip you with the skills and knowledge you need to effectively put lifestyle medicine into practice on a daily basis in your consulting rooms and to support those who are facing challenging circumstances, because it is these patients who have the most to gain. I look forward to sharing details of this content with you shortly.

References

- Morris, E, Aveyard, P, Dyson, P, et al. A food-based, low-energy, low-carbohydrate diet for people with type 2 diabetes in primary care: A randomized controlled feasibility trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020; 22: 512– 520

- Figures from socialmetricscommission.org.uk/

Login

Login